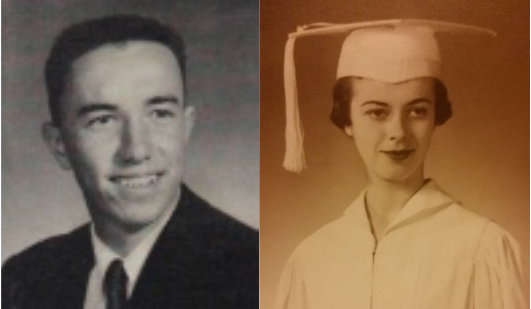

Last September I lost my mother.

She died unexpectedly one day, all at once. She was my last living parent, as my father had passed on a few years before.

My father did not die unexpectedly. His body had been ravaged by cancer. It spread throughout his body and his death was drawn out and painful.

The grieving process for my mother is still ongoing. As one friend told me, all kinds of things were going to make me sad for some time, and they do. Running the Nitro Turkley Trot in Point Pinole without her was hard to do, and going to Folsom during the California International Marathon was even harder, as she always came along so we could go to the shops on Sutter Street and have lunch at the Sutter Street Grill, and she would meet me at the finish line.

There are all kinds of things that make me miss my mother. When I see cute animal videos on TikTok and wish I could show them to her, and when I watch shows like Good Omens or The Marvelous Mrs Maisel and wish she could see them, because I know she would love those programs. And I when I do the things that we used to do together, such as when I go to Berkeley and pick up some scones and bialys at The Cheeseboard and get a Latte, which is what she and I would do whenever we went to downtown Berkeley together.

When my dad died, my reaction was completely different.

When I found out he had passed on I literally thought to myself, “See you in Hell you son of a bitch!”

My father was a self absorbed man with a violent temper.

And he made my childhood hell.

When I was a child I thought my parents were adults. It was not until years later I came to the realization that I was really raised by kids, young adults who were still figuring things out and didn’t know as much as they thought they did. They were also the kind of people who were not prepared for some adult responsibilities, particularly when it came to raising children.

As a child I was subject to a lot of abuse. Emotional abuse, physical abuse at the hands of my father who roughed me up more than a few times, and virtually non-stop verbal abuse. My parents would get very upset if I ever displayed any negative emotions. If I was ever angry or outwardly sad they would get unwound and give me hell, especially my father. It was a hellish catch-22. Given the way I was treated, sadness, anger, and fright were the only reactions I could muster because of my circumstances. How could I be a happy and content child when I was getting smacked around and being perpetually criticized by my parents? Displaying those emotions only stoked the fire of abuse.

My father frequently spanked me and my brother, or simply smacked us around. He would also pick us up and throw us across our room, the caveat being that he would throw us onto our beds, rather than against the floor or wall. But the most egregious crime he ever committed is when he split my head open. When I was just five years old, he hit me so hard that I stumbled across the floor and my head ran into a metal handle on a kitchen drawer. I was immediately sent to bed after that attack. I lied down for a few minutes and then I felt something wet on my pillow. When I lifted my head my pillow was soaked with blood. My parents rushed me to the doctor after hearing my shrieks of horror.

My mother was a more complex case. She did frequently chide me, and could not handle me if I became upset, but she simply did not know how to handle an angry, sad, or frightened child. My mother tried to deflect me and my feelings, rather than react with pure anger as my father did. When I told her I was miserable she would sometimes snap “Everyone’s miserable,” meaning I was no special case. But her voice was one of frustration rather than outright hostility.

However my mother was not always dismissive and deflecting. She did things for me when I was very young, such as teach me to read at an early age. I was already reading James Thurber around the time my father smacked my head open. She introduced me to music, and I wore out Elton John and Beatles albums when I was six, listening to Goodbye Yellow Brick Road over and over again, and getting haunted by Eleanor Rigby, my first ever true earworm. And she taught me about science and prejudice. She explained the concepts of racism and sexism to me when I was very young.

My father never did anything like that for me or my brother. He would sometimes take us fishing, but he never showed us how to fish. Impatience was one of his most pointed characteristics. He never showed us how to assemble rods, bait hooks, or clean fish. He would even cast our lines for us, rather than suffer through the chore of teaching use how to do it ourselves. If we ever hooked a big fish, he would frequently grab the rod and reel it in himself, rather than let us fight our own fishing battle. Our main contribution during these fishing trips was to simply hold onto the fishing rod while waiting for fish to bite.

He also never introduced me to sports. I found sports on my own, becoming fascinated by football when I chanced to discover it on television, and coming to a revelation when I first saw Muhammad Ali. I have been a football fan ever since I came across a 49ers game, and I was entranced by Muhammad Ali. When I was a child I dreaded becoming an adult. Adults always did boring things, and talked about boring stuff and were just boring. Kids were interesting. They could be goofs and weirdoes and it was just fine. I didn’t want to become a boring adult. When I saw Muhammad Ali bugging out his eyes and talking in rhyme and making his future opponent bust out laughing with his antics, I was transfixed. I had never seen an adult act like that before. Muhammad Ali taught me that you can be unique, you can be yourself, and you can act like a goof, or a weirdo, or be whoever you are, even when you grow up.

Those were the kinds of lessons my father should have taught me. But that never happened. A lot of things never happened that should have happened, because my father was barely interested in being a parent.

When I was little older I was struck at how different my parents were. My mother was a voracious reader, going through book after book. She would also cook meals all of the time. My father was perpetually glued to the television set and would rather stop by a fast food or burger joint rather than make anything from scratch. My mother would oftentimes talk to me about things such as sex, books, politics, and philosophy. If there was ever a serious conversation to be had, it was with my mother, never my father.

As I grew up they still did not know how to handle me. One year, when I was a tween, we moved to a well-to-do suburb of the Bay Area and I was forced to go to Orinda Intermediate School. I say forced because the place was utter hell for me. I was used to some teasing and bullying at my previous schools, but it had never been as bad as at that place. I was a Berkeley kid, and the kids that went there were well-scrubbed suburban types. And as a weird kid from Berkeley I was target number one for being bullied. I was subject to non-stop verbal and physical abuse. Kids were spitting on me, kicking me, punching me, and raining non-stop insults on me. So I kept skipping school, running off and walking to the local outdoor shopping mall or to the subway to go hang out in Berkeley. My parents were completely perplexed. They asked me why I was cutting school all of the time. I told them that they kids there were tormenting me, telling them everything that was happening at that school. But they still did not understand. They had on blinders that they would not, or could not, take off when it came to me and my problems with that middle school.

The abuse I suffered at the hands of those students was hell. It was like going to a school full of people who were like my father at his absolute worst. But it didn’t stop at the school. My brother brought this friends by our house all of the time, and they started tormenting me in my own home: constantly breaking into my room, vandalizing and stealing my things, playing practical jokes on me, and showering me with insults and abuse, meaning I had to put up with the relentless hell even after I came home from that wretched school.

I practically begged my parents to stop them, to punish my brother or stop his friends from coming into our home, but they did nothing. In fact they started punishing me for complaining about it. Eventually they sent me to a psychiatrist. They pawned me off to a shrink because they didn’t want to deal with me and my problem. And he wasn’t a very good psychiatrist either. All of our sessions were non-productive.

The whole time I had to wonder, what was it about them that refused to listen to me? To have all of my explanations and protests fall on such deaf ears? Looking back, I believe it was because if they really did listen to me and took real action, they would have to do the one thing they were most afraid of: parenting. If they relocated me to another school or punished my brother or hauled my brother’s friends back to their parents and told them what they were doing, they would actually have to parent. Acting like true parents and do responsible parent things was something that they simply could not face. As for my mother, I cannot fully explain why she would be so reluctant to act. My father is easy to understand in that situation. He was loathe to go out of his way for anyone except himself, even in the case of his own children. Seen and not heard. He didn’t want to hear from me. He just wanted me to shut up and not disturb him.

When I was around fifteen my parents finally split up. They got divorced and my mother moved out of the house. I was elated. I knew even before I was a tween that they were a disastrous couple. My brother was devastated, in a scene of what could only be interpreted as rampant denial, but I was practically dancing. It was a joyous occasion and I felt an overwhelming sense of relief that I did not think I could experience. The pressure cooker stress of having to be in the middle of their dysfunctional relationship was finally over.

With that big life change my mother started to try and transform her life. She started getting more and more into spirituality. She studied Buddhism, and joined a Gurdjieff group. She was well versed in spiritual and religious subjects. When a friend of mine’s mother threw him out of her house, I told my mother that my now homeless teenage friend’s mother had been studying Sufism. She said “How could she be into Sufism when she’s so cruel to her own son?”

After the divorce my parents grew further and further apart from each other. And as much as my parents were so different from each other, it was the same for me and my brother. We are very different people. I am more like my mother, and my brother was far more like our father. After the divorce we grew farther and farther apart, to the point where I eventually severed all ties with him.

It was around the time of my parent’s looming divorce that I finally started to find myself, just a bit. My parents wanted me to go to Miramonte High School, the local high school where all of my middle school tormentors were going. I put my foot down. I told them that there was no way in Hell I was going to that high school with all of those rotten suburban Nazis. I declared, in no uncertain terms, that no matter how many times they threw me into that high school, I would run right back out. I would refuse to attend classes or do any homework, or even remain on the premises at all.

My defiance worked. They sent me to Berkeley High School instead. It was a long commute, but I did not suffer one bit in the long bus and subway rides, knowing it was keeping me out of the Orinda school system.

It was not long after their divorce and my starting high school that I started drinking and experimenting with drugs. Berkeley High was a very good place to get into those habits. I eventually developed into an alcoholic, and by my early twenties I was a legitimate speed freak.

It was not until I turned thirty years old that I turned my life around. I quit doing drugs, and eventually I realized that I had to stop drinking. I walked into my first ever Narcotics Anonymous meeting more than twenty years ago, and I’ve haven’t used since then.

This was also a time of stark discovery. It is oftentimes unbelievable, how one cannot see one’s own life for what it was. During my young adulthood I went out with a woman who was an incest survivor, and she was doing a lot of incest survivor work. As her partner I helped her along with that work, reading books, doing trauma and self-scare exercises with her, and I found out this kind of effort included a lot of my own self care and reinforcement as a partner of an incest survivor. In high school I had gotten to know many people who had been abused as children, but they were all survivors of sexual abuse, and I came to the idea that sexual abuse survivors qualified a person as having been an abused child. The idea that I myself was a survivor of child abuse never occurred to me, until I worked with my partner on her survivor work. It just hit me all at once, that I had been a survivor of child abuse, even though I had never been sexually assaulted. Considering what I went through, it’s just bizarre that I could not see myself that way. This self-revelation also gave me insights into how my mother was rooted in denial and emotional blindness during my childhood.

My getting clean and sober was not just a big change in my own personal life, it also created a seismic shift in my relationship with my parents. I started talking to my mother more and more, as she kept trying to explore herself and improve her life and her outlook. Shortly after I found my newfound sobriety I severed ties with my father. I stopped associating with him or speaking to him, because if there was someone who was not looking to improve themselves it was my father. He was still as abusive and dismissive and self-centered as when I was a child. And, basically, it turned out, I just couldn’t stand him when I was sober.

My mother and I started talking and meeting up more and more. We would eventually develop a ritual where we would grab some pastries from a bakery, get a cup of coffee, and then haunt a bookstore, one of our favorite things to do.

Later on my mother would tell me about her life regrets, specifically regarding our family life when I was a child. She told me that she wished she had taken me and my brother away from my father, the night after he split my head open. It would have been rough, she explained, because my father was the breadwinner. We would have had to live in very poor conditions if she had left him. She also said she was sorry that I had such an awful childhood.

And that made all of the difference. My mother did what my father never could: admit that she had made a mistake. In hindsight I can understand everything much better. My mother and I would basically have had to live in poverty if she took us away from our father. That was a dive she was not willing to take at the time.

It’s not like my father didn’t have the same chance. If only he could have admitted that he made mistakes, if only he could have admitted that he regretted what he had done, that also would have made a huge difference. But my father was incapable of ever admitting that he was ever in the wrong or had ever made a mistake, in all things large and small. When I was a child he would occasionally run into animals while driving. He was an impatient driver, as he did almost all things impatiently. When he did run into animals, he would offer complex reasons as to why he was not at fault. It was not his fault when he clipped a deer who ran across the road, and not when he ran right into a dog and badly injured it. And as horrible as he was as a father, he would never, ever admit that he had ever done anything wrong during my childhood. He was obsessed with always being in the right, no matter what the offense, even in the case of beating a defenseless child bloody.

My mother and I kept forging a stronger relationship. When I started writing, she not only read my works, she helped edit them. She is the only person who has read every one of my first six novels. When I started running footraces and began running marathons, she not only became my running support team by going with me to these races, she started running footraces herself, running 5Ks and 10Ks, and eventually I started meeting her at the finish line. We even ran a few races together, particularly the See Jane Run races and Nitro Turkey Trot every Thanksgiving. She even won her age group a few times. (Full disclosure: her age group oftentimes included just two or three runners, the over 70 group.) She loved running those races, and kept talking about how she wanted to run another race during the Covid lockdowns, even towards the end of her life.

This is the time I’m experiencing right now, when both of your parents are gone, when they’ve both left this world and you reflect on what they meant to you and what they did and didn’t do for you, and how they shaped who you’ve become. I am still grieving the loss of my mother, three months after she passed on. The tears don’t come easy, for some reasons I am well aware of, and for other reasons which I am still working out. One of my overriding feelings is regret. Regret that I couldn’t do more for her in her later years as she struggled with finances and rebuilding her house, regret that I never had a stable enough life to give her one thing she always wanted: a grandchild. The grief gets more pointed during Holidays and footraces, and going back to my native Berkeley is a lot emptier without her around. She went from a neurotic mess of a mother to becoming the one person I could always really rely on in my adult life.

Thinking about my father, his passing was a relief for me. He was finally gone. No longer was I in danger of suffering his toxic attitude, his hair trigger temper, or his constant scorn. But the memory of him still produces strong emotions: anger, regret, and resentments so strong that they are in danger of sending me into a rage, a rage not unlike one of the many furious outbursts my father. The one thing my father really gave me: A bad temper. It’s something I’ve worked on and improved on over the years.

I left a lot out in this essay. There’s so much more about this personal history that I could write about. It could fill a book. Maybe some day it will. But writing all of this out right now is part of my personal catharsis. The vast enormity of death is the deepest well of reflection. I have made myself look at what they left of themselves in this world, now that they are gone. For better or worse, I am a big part of their legacy, especially now.

Thanks for sharing your story, it is very interesting. I’m sorry for the abuse.

You are so strong and your emotions are valid! Much love.

Your story is poignant one, well-told, and impactful. Our childhood affect us. Our childhoods shape us. The memories shape us and I loved seeing how the earliest stages of your life brought you to this: sharing an important story to help open eyes to the nature of abuse.

I am sorry for the lost of your parents. I hope you have found healing and continue to heal from your childhood trauma. Thanks for sharing your experiences.

Thank you for sharing. They say that the child is the father to the man. Hope you are well.

Thank you for sharing this, I’ve had a similar journey myself and only recently did I think of what I went through as a form of child abuse. I cut ties with my dad last year, although I have tried this on the past, I feel it will stick this time. I hope you’re very proud of all you have come through and achieved, you are very strong x

Thank you for exploring this so openly; it was poignant and raw and described the intricacies, challenges and complications of your family life with beauty. I wish you well as you, no doubt, continue to reflect on these experiences and relationships.

Wow, what a post! Thank you for sharing all of this with us. It must have been difficult to have to think about all of this again. Take care of yourself.

I feel you, my friend. My dad died when I was 19, way too young to have a chance to get to know who he really was. My mom was a depressive, “covert” narcissist who appointed me co-parent and confidant when I was 14, after they divorced — which, as you might imagine, really messed up our later relationship. There were years that we did not speak. She became a little nicer with dementia. But when she died of COVID two years ago, it was a relief. I try to learn from her mistakes so as not to perpetuate suffering in the world. But I envy you the relationship you forged with your mother in your adulthood. Sometimes I wish I could have had that with my dad. But I can say your mom was proud of who you are, and you do her proud. I’m in awe of your creative efforts and willingness to put yourself out there. (I can’t do it.) I can see why you were Jamai’s friend. You’re worthy of knowing, Jeff. I see you.

Aw Jeff I Hope getting these words out helps you heal. You carry a heavy load. Dropping those stones one by one will really help. I’m sorry I’m not more available than I’ve been to connect. We all have loads to carry I guess. But you’ve really lost a big part of your world. I know that is hard to recover from. Love to you.